And God placed the middlegame before the endgame

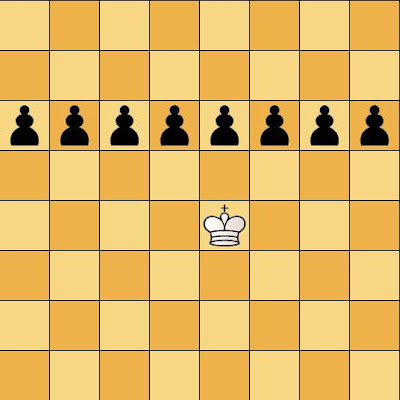

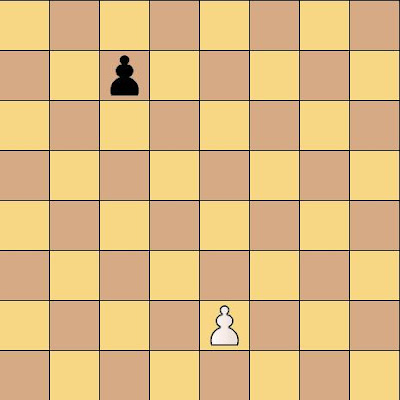

Phaedrus added the following comment to my latest post: "It is completely unclear to me why an "ideal game" should end with an endgame. It might well be possible that the ideal game (played by the super computer that "solves" the game of chess, is already decided in the middlegame. As your assumption of an ideal game is the foundation of this quest, I do not know if you have struck gold here. Yet I am very interested to see where it ends. " Disclaimer: warning, abstract ranting ahead! There are 3 ways by which a game can be won. Winning a piece Mating the King Promoting a pawn All combinations that win a piece can be devided in two seperate groups. The first group I have dubbed the duplo-attacks . These work by attacking simultaneously 2 pieces with only 1 move. Notice the similarity with my previous posts where one move served two goals. If the opponent of whom 2 pieces are under attack can only make a single-purpose move, he can only save one piece by ...