Pawn battle

After the adage of Philidor "the pawns are the soul of chess" I used to add in my mind "yada, yada, yada".

But finally I understand what he was talking about.

The pawns determine what the scope of the the pieces is. They restrict both your opponents and your own pieces. This means, that the battle of the pawns decide which pieces are going to get more scope, and which pieces are getting restricted.

Now the goal is clarified, it is time to get more insight in how that mechanism works. Since Lucas Chess don't let me create boards without kings, I cut the board in half, so we are not being distracted by irrelevant variations that accidently emerge.

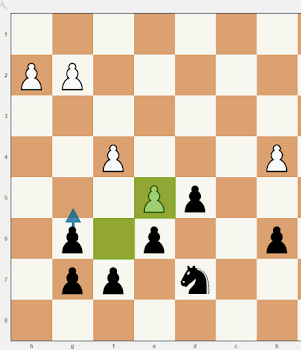

|

| Diagram 1. White at bottom |

In diagram 1, white wants the juicy outposts e5 and g5 for his knight. By pushing g4-g5, he undermines the black pawn on f6. Black has 3 options:

- f5

- fxg5

- do nothing

In all 3 scenarios, white gets the upperhand on e5 and g5.

|

| Diagram 2. Black at bottom. Black to move |

Instead of directly attacking the pawn that you want to disappear, you can undermine it by attacking the defender.

1. ... g5

2.g3 gxf4

3.gxf4 g5!

And e5 will become available as pivotal point for the knight.

|

| Diagram 3. Black to move |

Sometimes, opening up a LoA can have an effect on pieces of both sides. In that case, you have to judge who is going to benefit the most from the opening of the position.

In diagram 3, black will play f5, in order to undermine the defender of d5.

White lags behind in development, and it is too dangerous for his king to use f2 as a defender of e4.

Blacks light squared bishop will profit more from the disappearance of e4 and d5 than whites bishop. Blacks pieces are ready to jump on the free coming LoAs (lines of attack), while white has trouble to develop his rook and to coordinate his pieces. Black takes the initiative, and forces white to answer his attacks instead of working on his development.

In the opening, you need to be aware which LoAs are about to be opened and take care that you don't open LoAs when you are not ready yet.

It is not rocket science, but it sometimes can be subtle to judge.

An alteration of Diagram 1, adding the two Kings (to allow GM Stockfish to analyze the position):

ReplyDeleteFEN: 8/5b2/1k3pp1/3p4/1K1P1PP1/5N2/8/8 w - - 0 1

Given that both sides have a pawn phalanx (the strongest position for a pawn duo), the player to move (in this case, White) can favorably alter the pawn landscape due to the somewhat “accidental” location of the two minor pieces. The two Kings play no role in this “dance.”

White would like to accomplish the following micro-objectives:

(1) Prevent an unfavorable shift in the pawn structure. The mobility of Black’s Bishop is somewhat restricted by the BPd5 and the BPg6. Unfortunately, Black cannot advance BPg5 because White controls it [2:1]. Advancing the BPf5 would be bad because the Black Bishop would be even more restricted in mobility, and White would be given two beautiful outposts on e5 and g5.

(2) Obtain an outpost (better position) for the WNf3. The only means for doing this (absent any other pieces) is to advance a pawn, forcing Black to either capture of advance his pawn to avoid capture.

Logically, White should advance g5 because that square is controlled by White and, whether Black captures or advances to f5, White will have improved the potential for the WNf3 with an outpost on e5 and (potentially) an outside passed pawn.

I tried various balanced positions for the two Kings, and after at least 15 minutes calculation, GM Stockfish evaluated the position as 0.0, whether Black captures on g5 or advances to f5.

The fact that the positions before and after are balanced (totally even, with best play for both players) is not the point (for me).

It is the very essence of positional play to accumulate small (tiny?) advantages whenever possible. White puts the onus on Black to decide which concession he will have to make: allow a more advanced outpost for WNf3 or put his pawns on the same color as his Bishop.

If following the “rulez,” then Suba’s “rule” might be followed by Black:

“Bad bishops protect good pawns”, advancing to f5. Yes, White can “attack” the BPg6 with his Knight, but because of the relative King positions and the pawn structure, there is no way for the White King to sneak into the Black camp. The White Knight cannot gain a tempo on the Black Bishop, and there is no Knight sacrifice available to get an unrestrained passed pawn.

The interesting “fact” is that White has no square from which he can attack both BPd5 and BPg6 simultaneously with WPf4.

As part of studying this position, I back went into Nimzowitsch’s My System, Part II, Chapter 1, Prophylaxis and the centre.

He emphasizes that prophylaxis (anticipation of problems) applied both to moves by the opponent (external) and to our own position (internal) is the most important aspect of positional play. The accumulation of tiny advantages is only the second (or perhaps third) most important aspect.

What is important above all is to head off certain positionally undesirable possibilities before they materialise).

Excluding blunders, there are only two types of such possibilities.

(1) Allowing the opponent to make a “freeing” pawn move.

(2) Taking measures to prevent some problem which can be extremely disruptive. This problem is that our own pieces are either not in contact with or are in insufficiently good contact with our own strategically important points.

”Weak points, and even more so strong points, (in short every point which could be described as strategically important) must be overprotected! The pieces which fulfill this duty are rewarded for helping to overprotect the said strategically important points by the fact that they are well-placed when it comes to undertaking other duties; so to express it somewhat dramatically, the importance of the strategic point envelops them in its halo.”

Thus spake the Maestro.

I used to prefer a bishop over a knight. But since I play the French, I have learned to appreciate the good knight against the bad bishop.

ReplyDeleteI notice that you have found other ways to get distracted ;)

When your knight is more active, you have chances to get the initiative. Your knight attacks the weak pawn g6, while the bishop is tied to the defense (Fun), delivered at the mercy of the knight.

When you set up a second front, as advised in any endgame book, your active knight can leave its attacking function at will and jump to the second front, while the bad bishop might have trouble to follow in time.

The advice of Stockfish in these type of positions can be very misleading. Since the bishop cannot leave its position freely due to is defensive duties, white can play for a win without risk, while black may have to find a series of only moves to stay afloat. Something that is not easy in practical play when you are not Stockfish.

The push of an (over)protected mobile pawn is essentially a dual purpose move. A discovered attack. The pawn moves, and does something awkward, and leaves in its wake a pivotal square or an open line.

That's a minor "distraction" compared to my recent object of attention. I think I have a good explanation (hypothesis) for the "trick" that child prodigies seem to easily master intuitively, and why adult chess improvers CAN (but rarely do) learn that "trick" — it's pretty far from the beaten path and a galaxy away from what you are currently investigating, so I won't discuss it further here.

ReplyDeleteAs usual, I may only be deceiving myself, but the explanatory pieces all seem to fall into place so far.

So many worlds in the multiverse to explore and so little time to do it in!