Skill times Knowledge

I start to get a pretty good idea where my boat is leaking. I use my own games to have a good look at the leaks at both sides. There are different areas that need attention. The first division in type of categories is skill and knowledge.

I postulated that Result = Skill x Knowledge = How x What

Furthermore, I postulated that skill is the fundamental "trick" that makes child prodigies to become grandmaster at the age of 14. Whereas the knowledge is provided by their coaches.

Both Skill and Knowledge have their own problems.

Recently, I'm studying Birds and Latin vocabulary with the aid of Anki. I noticed that in both studies I suffer from the same problem, which I will call the "priest problem" from now on. It is the problem that you need to add more energy during the learning process. To begin with Latin, there are words that are hard to learn because they seem unmeaningful, and no associations are coupled to them:

- nam

- etiam

- tum

- quot

- num

Etcetera. As you see, it are often short words, there is not much to go on, and it is difficult to find an association.

For bird sounds, it is even worse. The sounds are often sounding the same, there are songs, calls, alarms and different reasons for birds to produce sounds. And we have no language to base an association on. Furthermore, there are good imitators among them.

To learn these difficult to learn items, you must add sufficient extra energy to the learning process. You must take a resilient flashcard, and decide not to click it away before you are sure you know it. You must build artificial associations, even when there aren't any natural ones. And before all, you must keep an administration of the mistakes and realize that you cannot go any further before you absorbed them.

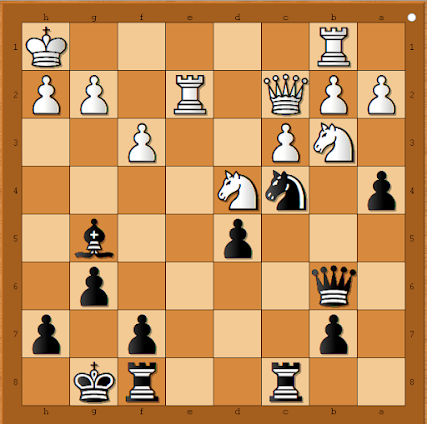

The next diagram is from my own game. I played black and have just threatened my opponent's knight with 20. ... a4

|

| BE AWARE! White to move! |

2r2rk1/1p3p1p/1q4p1/3p2b1/p1nN4/1NP2P2/PPQ1R1PP/1R5K w - - 0 21

After 5 minutes of thinking he played 21.Nd2??

Which is a blunder, ofcourse. Why did he make this blunder? Usually he is very good at counting defenders and attackers. That is the skill he used. On d2 his knight is attacked twice and defended twice. But what was not in his skill, was that he wasn't able to SEE that the defenders cannot defend at all because they have too high a value.

The hunt for skill is based on hunting for these type of skills. If you don't realize you have a problem, you will not give the subject enough energy. It is like a flashcard which you click away without absorbing it. And my opponent can be sure to make this mistake again.

The skills you need to obtain are not rocket science. But before you can obtain them, you must know what exactly the problem is. What did you miss and and why did you miss it? And be sure to add enough energy to the solution so that you won't make this mistake again!

Of course my opponent could have calculated the move. That would have disguised the lack of skill, and the problem would have gone by unnoticed. But blundering and ignoring the problem is even more hideous. Yet that is what we do all the time.

Knowledge

Earlier in the game I was saddled with an isolani. The moment I noticed it, it was too late to prevent it.

|

| BEWARE! White to move |

This happened after

- 1. e4 e6

- 2. d4 d5

- 3. Nd2 c5

- 4. exd5 exd5

- 5. Ngf3 Nf6

This showed a leak in my boat. After 4.exd5 I can safely take back with the Queen and avoid the isolani.

But that is not what I wanted to show you. After the game, we talked about the isolani, and he started to recite some platitudes from GM Euwe about it, like "you don't need to worry about getting an isolani, there is still a lot to be played for", or something like that.

Well, that was not my first problem, I don't mind an isolani, when I choose for it deliberately or when I cannot avoid it. That was not the case here.

The problem for my opponent was, that his knowledge about the isolani was in fact pseudo knowledge. Since he had no real idea how to play the position. I immediately shifted gears, and started to avoid any trades and to add all kinds of pressure to the position.

It shows that a lot of our knowledge is in fact pseudo knowledge. It prevents us from digging deeper because we think we already know.

And it is always easier to see what other people are doing wrong than to look at ourselves.

Btw, beware of the priest problem!

“Those people who think they know everything are a great annoyance to those of us who do.” ― Isaac Asimov

ReplyDeleteI asked Bing Copilot for an explanation of the phrase “Give it up; don’t just mail it in.” I’ve often heard this phrase used by musicians when encouraging their band mates to be fully engaged, regardless of how small the venue or audience.

The phrase “Give it up; don’t just mail it in” carries a powerful message. Let’s break it down:

“Give it up”: This part of the expression encourages persistence, determination, and wholehearted effort. It means not surrendering easily, continuing to strive, and putting your best foot forward.

“Don’t just mail it in”: The second part emphasizes that mere complacency or minimal effort won’t suffice. When you “mail it in,” you’re doing the bare minimum, lacking genuine commitment or passion. It’s akin to sending a task by mail without being actively present or fully engaged.

So, when someone says, “Give it up; don’t just mail it in,” they’re urging you to give your best, invest genuine effort, and avoid settling for mediocrity. It’s a call to action, reminding you not to take shortcuts or coast through life without passion and dedication.

Is this what you refer to as the “priest problem”?

Yes. With insufficient engagement your system 1 decides not to assign long term mental resources to the problem. The priest used a cheat sheet for 25 years. Which in fact requires a greater effort than a few evenings cramming with full engagement.

ReplyDeleteFor full engagement you need energy of another level. It feels easier to use low level energy for a long time than to use high level energy for a short time. But you can't ignite a lucifer by warming it with your hands. No matter how much time you invest in it.

I guess that "out of your comfort zone" and "deliberate practice" refer to the use of high level energy. That is needed to initiate the plasticity of your brain again.

lucifer should read match.

DeleteCalculation camouflages that you lack skill.

ReplyDeleteI searched backward to find your earlier reference to the “priest problem”:

ReplyDeleteThink of the priest who needed a cheat sheet for his prayers. His horizontal effort of 25 years reading the daily prayers was immense, while he was too lazy to make the little vertical effort to learn the prayer by heart in a few evenings.

Given a cheat sheet, I suspect there was little mental horizontal effort involved. That’s a cautionary tale for us adult chess improvers!

“Familiarity” with the literal meaning of B.A.D. (an equal number of attackers and defenders on a particular square) is necessary but insufficient for “SEEing” a B.A.D. pattern in a specific position and ALL the ramifications (like the relative value of the piece used in the potential capture sequence).

As the old saying goes, “Familiarity breeds contempt.” Perhaps that “contempt” is also a manifestation of laziness. We are too often content to acquire a rudimentary understanding of a concept, especially when it comes with an easily recognizable catchy label [B.A.D.]. As a result, we STOP trying to discover (recognize) and understand ALL potential nuances of the conceptual abstraction when applied in different circumstances.

Maybe this is what GM Davies meant by “You have to move the pieces around and SEE what happens; amateurs don’t do that, but GMs do.” We “assume” he meant trying different variations (the literal meaning of “moving the pieces around”). Perhaps he also meant trying to acquire a broader grasp of a particular concept by gleaning ALL of the nuances from every specific position. The best time to acquire a more nuanced understanding is the moment we encounter a nuance that is different from what we expected based on our knowledge. I know I have experienced little jolts of AHA! after recognizing a new nuance. It is those moments that are very important to recognize and store in long-term memory as part of our “vocabulary.”

The preceding paragraph is an excellent example of broadening a concept beyond the “obvious” literal (rudimentary) level!

I have a set of 111 tactical problems which are rated about 1700. I repeat them at a very slow pace. Say two or three days for a circle by now. In the beginning it took me a day per problem. During every circle I discover new things. I'm at the 27th circle now. Instead of becoming boring, it becomes more interesting.

ReplyDeleteI like to think of Davies moving the pieces around as getting into a position and Moving the Furniture.

ReplyDeleteWow 24 times. I am finding that doing the CT.art 5x5 squares and reading Understanding Chess Tactics. I am learning more. I am on and off again with these circles. I had a 2 year break. I dont know if it is true but I heard research points to a good time for doing a spacefd repetition cycle is when one is close to almost forgetting.

ReplyDeleteThe "bible" on deliberate practice is the book PEAK: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericcson and Robert Pool. They carefully distinguish between purposeful practice and deliberate practice. The most obvious differences are:

ReplyDelete(1) Deliberate practice always takes place at the edge of competence. You find out what you cannot do, and what is required to do THAT, and then you practice THAT.

(2) Deliberate practice requires a coach for the fastest way to reach competence, because a coach can diagnose problem areas and provide training solutions. It can be done without a coach but there will be a lot of false starts (and thus wasted time) before the correct solution can be found. Most people have neither the time, the interest nor the perseverance to work everything out from first principles for themselves.

The example of Benjamin Franklin is an outstanding case study in the book. The authors detail the self-created [deliberate practice] method whereby Franklin became a master of writing. They also detail why Franklin never became a first-class master of chess. He never thought to adapt his successful method for gaining writing skill to chess. It shows that sometimes looking across subject “boundaries” and applying methods from one subject area to another can be very fruitful. Unfortunately, in our “age of specialization” we are rarely given examples of breaching the walls of the “silos of knowledge.” For instance, there are tactics and strategy, positional and combinational play, openings, middle games and endgames, etc., and we “must” approach them separately—and then “hope” that by some miracle they will automagically coalesce into overall skill.

Spaced repetition is covered in the book, and you are correct: repetition should occur right near the edge of forgetting. The primary reason is that it will take more effort to recall, and it is the repeated effort that cements the learning into long-term memory as SKILL.

As Temposchlucker noted above, applying focused attention and energy enables memory and, most importantly, provides new insights into "interesting" nuances that will NOT be seen during the first iterations. First "SEE" the obvious broad contours, and then refine the conceptual space with finer grained details on each subsequent iteration. There will always be something "new" to "SEE" in non-trivial positions, no matter how many iterations are performed. The "key" is to LOOK for similar or related concepts using analogies.

It are not iterations for the sake of iteration, like with the 7 circles of madness. I just study the problems in a convenient way and at a convenient pace. It is only the counter of ChessTempo that told me that iterations have happened. I wasn't aware of that.

ReplyDeleteBy digging deeper in the problems, the less deeper layers are absorbed automatically. Since those levels I SEE at an instance when I study the problem again.

And the deeper I dive into a problem, the more simple it becomes. Which might sound counterintuitive at first, but which is perfectly logical.

The question is, how rich is the set of 111 problems I use in tactical elements, and what is the frequency of occurrence of those elements. And does my method transform knowledge into skill? To begin with the latter question, I'm inclined to think so. Because whenever I encounter a problem again, I SEE more without the need to think.

The problems differ wildly. So the frequency of occurrence of the tactical elements is a serious issue. I reach the stadium that this is my main concern. I try to figure out how the problems relate to the standard scenarios from the PoPLoAFun scenario tree. This places the tactical elements on a higher conceptual level.

No matter whether such small problem set is rich enough, I need to create a base level anyway. So I create a base and trust that I get a sign when new problems are needed. Until then, I just dive deeper in the current set. Since it is still quite interesting.

23 of the past 24 years were mainly used for finding out a method that works. Becoming my own coach took a lot of time.

ReplyDeleteI guess that when a child prodigy runs out of coaches, he will encounter the same problem. In the end, he must become his own coach. I expect a lot of them to fail in that department.

Thanks Robert & Tempo.. I am picking up something each pass through. I am interested in how pieces are lured off the back rank to capture . Then forced to block a rook check. on the 8th rank .the attack now has a tempo to play with.

ReplyDelete