Re-engineering

A few years ago I did the course "100 endgames you must know" from Chessable. I quitted halfway.

The reason for that, is that I learned the moves, but not the understanding. The Movetrainer of Chessable invites you to do so. But that is a stupid use of the Movetrainer.

What we learned from the post of July 21th, is the power of logic. Two totally different positions could be solved with the same logic: "chase the slowest piece (the king) into a duplo attack".

This means that logic is the answer to the transfer conundrum, how to transfer knowledge that is learned in one position to another position.

To formulate the logic in a position costs more energy than just to learn the moves. But the moves fade from memory within two years, while logic last much longer, often even for life. When you only have learned the moves, you can be helpless if the position is even only slightly different.

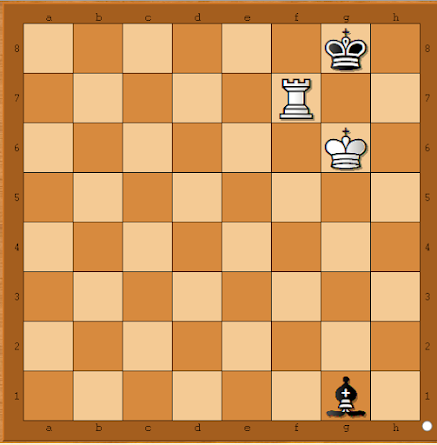

|

| White to move |

6k1/5R2/6K1/8/8/8/8/6b1 w - - 0 1

Here again, you need the end position first, and re-engineer the moves from there. What is the end position? What do we want to achieve?

What are the constraints for a move to get there?

- We must keep the black king where it is.

- We can safely chase the bishop.Since when we threaten the bishop, black has no time to save his king

- The bishop must be able to keep the rook from the back rank

- The rook cannot afford to lose a tempo, since then the black king has time to escape

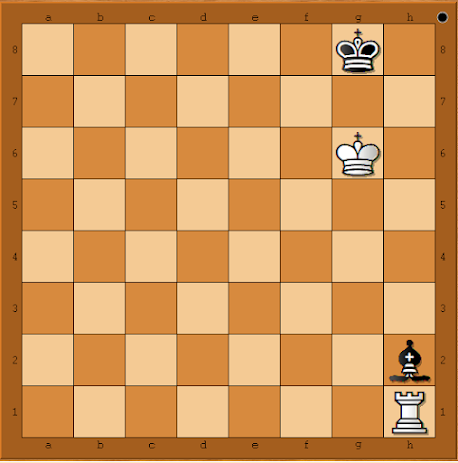

|

| Black to move |

Here it is time to fiddle around with the aid of Stockfish. All based on the question "what if?". Fiddling around has a lot of similarities with trial and error. There are two important differences though:

- You limit fiddling around to the study room only

- You fiddle around until you can draw a conclusion. Without a conclusion, the fiddling around is useless

The child prodigy fiddles around and the amateur uses trial and error. So what is the difference?

ReplyDeleteThe child prodigy, under the leadership of his coach, draws a conclusion and stores that.

While the amateur goes hastily to another position and forgets to draw a conclusion from it. Making the same mistakes year after year.

So what did MDLM and Stoyko do but forgot to tell us? They drew logical conclusions and stored them. That's why their methods worked for them and not for us.

DeleteI entered the position into Chess Tempo and found that 7 games reached this exact position, with 100% won by White.

ReplyDeleteI have an idea why this position was included in the course "100 endgames you must know." It is to illustrate the logical process that you have discovered, as well as the fact that K+R vs K+B may be won or drawn, depending on the circumstances.

I did a search for “chess endgame rook versus bishop result”. There are some interesting videos and articles available.

Bing’s Copilot had this to offer:

In chess, the endgame of rook vs. bishop can be quite intricate. Here are some key points to understand:

General Outcome: This endgame is typically a draw if both sides play accurately. However, the rook has better chances of winning compared to the bishop.

Key Strategies for the Rook:

Cornering the King: The rook should aim to drive the opposing king towards a corner of the board that is the same color as the bishop. This limits the bishop’s mobility and increases the chances of checkmating the king.

Cutting Off the King: Use the rook to cut off the opposing king from escaping to the center of the board. This can be done by placing the rook on a rank or file that the king cannot cross.

Key Strategies for the Bishop:

Opposite Corner Defense: The bishop should try to keep the king near a corner of the board that is opposite in color to the bishop. This makes it harder for the rook to deliver checkmate.

Centralizing the King: The bishop should work to keep the king in the center of the board where it has more mobility and can avoid being trapped.

Common Techniques:

Philidor Position: This is a well-known defensive setup where the defending king and bishop work together to prevent the attacking king and rook from making progress.

Cochrane Defense: Another defensive technique where the defending king stays close to the bishop, making it difficult for the rook to deliver checkmate.

I guess the relative importance of this endgame knowledge is subjective.

For me, the frequency of occurrence is leading. 7 in a gazillion is a waste of time as long as there are more frequent positions that I don't master.

DeleteI did like to uncover the details though. There is a lot of invisibility for the untrained eye. That makes any endgame a mighty weapon. An empty board with invisible structures.

I revised my opinion. The logic is general and interesting enough of these types of problems. Pins and skewers are quite commonplace in endgames. And it is all about seeing those patterns on a board that is only seemingly empty.

DeletePART I:

ReplyDeleteHere is Capablanca’s reasoning regarding the relative importance of studying the endgame prior to studying the opening or middlegame.

The Chess Legacy of José Raoul Capablanca: Last Lectures, Chapter One: The Importance of the Endgame:

“In learning to play chess well it is helpful to divide the game into three parts, to wit, the opening, the middlegame, and the ending. Each one of these parts is intimately linked with the others, and it would be a grave mistake to study the opening without keeping in mind the subsequent middlegame and ending. In the same way it would be wrong to study the middlegame without considering the endgame. This reasoning clearly proves that in order to improve your game you must study the endgame before anything else; for, whereas the endings can be studied and mastered by themselves, the middlegame and the opening must be studied in relation to the endgame.”

“This obvious fact has been ignored by almost all of the chess authorities, with dismal results for the great mass of chess players. Thus, for example, you find innumerable works on the openings, wheres there are hardly half a dozen books on the endings. In addition, almost all the books on endgames are little more than repetitious collections of various endgame positions without notes of any kind or with very inadequate ones. The result is that the majority of players who undertake to study the endings soon discover that they lack the necessary aids which would enable them to derive some benefit from their labors.”

“In these pages I shall try to make up at least partially for those deficiencies. You must always bear in mind that, as I see it, you cannot have a well-grounded understanding of the opening, nor can you satisfactorily appraise a great many of the current opening variations without an adequate knowledge of the endings.”

PART II:

ReplyDeleteI ASSUMED that his reasoning was based on the endgame being relatively simpler than the earlier phases of the game. In light of your recent conclusions regarding logical scenarios and backwards thinking, that is just WRONG. Instead, it is the idea of knowing where you are going (ie, the specific goal, based on the concrete position) and the process of discovering how to get there (augmented by pattern recognition along the way) that can best be studied in endgame (or at least simpler) positions. It is the process of discovering the 2-3 tactical themes/devices that are inherent in the specific position, and the logical connection of those themes into a favorable variation leading to the final goal—which must be determined BEFORE trying to find a logical sequence of moves to reach it.

In short, having a goal and determining the available means to reach that goal is the very essence of logical planning, regardless of whether it is categorized as strategical, tactical or positional.

Perhaps we have been too hard on MdlM, Stoyko and other pedagogues who have tried to give us signposts pointing toward the training that is needed in order to improve our skills beyond “average.” The idea of SEEing a logical goal (inherent in the specific position) and then thinking backwards to how to get there from the current position might have been as ‘obvious’ to them as it was to Capablanca—and therefore not worth pointing out to the masses of players for whom it is anything but ‘obvious’. Or, it could have been as hidden from them as from the rest of us, although it has always been there, “hiding in plain sight.”

“There are none so blind as those who will not SEE!”

Rhetorical question: If this training process is so ‘obvious’, why did it take all these years of hard labor to SEE it?!?

In any event, I have changed the way I study tactics (regardless of the type of position with respect to the three phases of the game). Whether I correctly solve a specific puzzle or not, I try to go back through the entire game in order to determine WHY a combination came into existence at that specific point in the game. In far too many cases, it is simply a blunder on the part of the loser, not the result of a profound strategy culminating in an inexorable tactical denouement. That is sufficient to explain the LPDO result from GM Nunn. You can’t play (or avoid playing) what you cannot SEE!

I ASSUMED that his reasoning was based on the endgame being relatively simpler than the earlier phases of the game. In light of your recent conclusions regarding logical scenarios and backwards thinking, that is just WRONG. Instead, it is the idea of knowing where you are going (ie, the specific goal, based on the concrete position) and the process of discovering how to get there (augmented by pattern recognition along the way) that can best be studied in endgame (or at least simpler) positions.

DeleteI don't think that simplicity has anything to do with it. Since you cannot develop a middlegame strategy without knowing which endgames are winning and which not, you MUST first know that.

Before you can develop an opening strategy, you MUST know what type of middlegame you want to have.

The only way to escape this iron rule is to mate your opponent before you reach the endgame. As far as I know, an endgame of some sort is reached in 60% of the games.

Currently I try to solve the following conundrum. I found two rules:

ReplyDeleteThe pawn structure dictates the piece placement (Seirawan)

Pawn moves are dictated by piece placement (Kabadayi)

How to combine this?

To me, it’s the difference between initial development and subsequent attack/defense in the middlegame. Both ‘dictates’ are valid—at different stages of the game.

DeleteInitially, the pawns must be advanced to facilitate the development of the pieces. This involves the attempt to control the center (in one form or another, ie, by occupation with pawns or by remote control by pieces) and, concurrently, the most critical lines of attack based on the pawn structure. Consequently, the opening pawn structure effectively dictates where the pieces can/should be placed to support the center and for subsequent attacks, ie, the tabiya.

After that initial deployment, anticipated attacks often require additional pawn moves to gain space, open lines of attack (pawn breaks), set up outposts or to limit the opponent’s mobility and potential for attack and defense.

It is all about shifting the attention from the MOVES towards the WHY of the moves. Why = logic. And the logic always turns out to be more piece position independent and general. It is this generalization that takes care of the transfer of knowledge from one position to another. Together with the frequency of occurrence.

ReplyDeleteThe coupling between the why and the patterns are the chunks that are stored. This creates the interaction between system 1 and system 2. Patterns trigger logic and logic triggers patterns. This leads to a twofold approach. The logic (system 2, forward) acts as a guide for the attention and the educated eagle (system 1, backwards) shows you the goals.

Since system 1 is so much faster, our pedagogues tend to overlook this aspect when teaching us. Oleksiyenko even says this in a video. He doesn't use an algorithm himself, he solely invented that for his students.

DeleteMe: forget the moves and the variations. Just focus on the WHY.

Notice how comparable it is to speech. The slow verbal forward development of a sentence (system 2) and the constant unconscious peek into the future by system 1 to retrieve the goal whereto the sentence is heading.

ReplyDeleteThe fast speakers have alot of future goals absorbed. While the slow speakers tend to create their goals on the fly (trial and error).

ReplyDeleteThe fast speaker must have simplified the world beforehand. Otherwise there are too many goals. That is the benefit of bias. It simplifies the world.

In order to be creative, you must drop your bias. Since bias limits you to a finite amount of goals. By dropping your bias, you drop your speed.

What can go wrong here? Your bias can be wrong. Or you never get to formulating a new goal (getting stuck in trial and error).

Trial and error is good. Trial and error = fiddling around. But you MUST come to a conclusion and store it. Otherwise it fades away.

ReplyDeleteMake sure your conclusions are CORRECT. Conclusions simplify the world. That is the way to speed up your mind. When you run out of new conclusions, you plateau. When other people draw new conclusions and you don't, you will be overtaken.

ReplyDeleteThere is your free lunch: borrow or steal conclusions from other people. Karma requires that you pay for your lunch, btw. One way or the other.

ReplyDelete